To name a place is to choose both its distance and its detail. How near it feels, and how clearly it comes into view. Years ago, while collecting all the toponyms of a mountain I had looked at countless times, I realized I had never truly paid attention to most of them, nor had I ever wondered what they meant. Perhaps that’s how we all come to know the names around us – taking their existence for granted, as if they had always been there, even before the place itself took shape. But what began as a linguistic exercise soon became a visual one. Words, long before maps and images, make use of resolution and scale to describe the visible world.

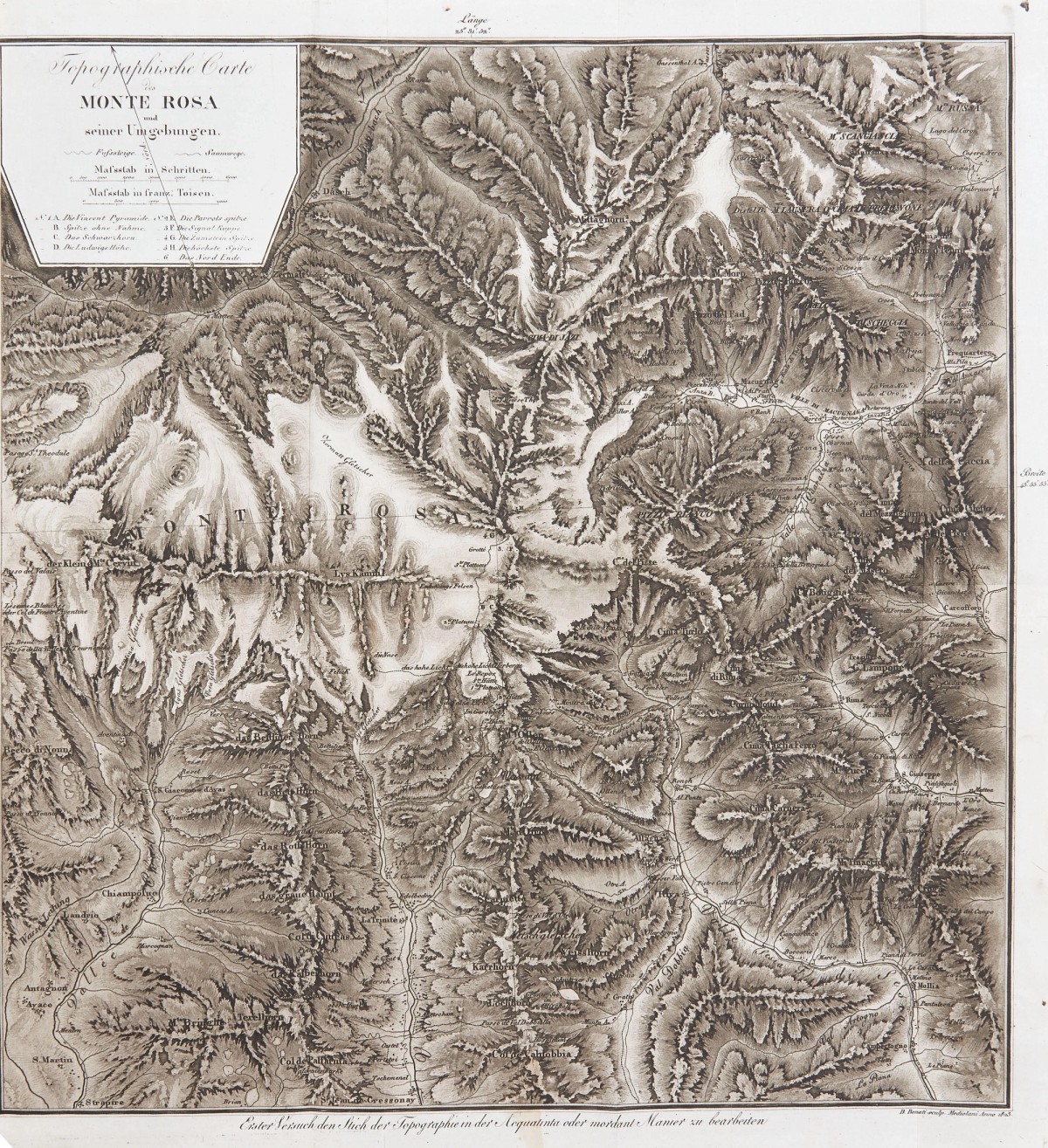

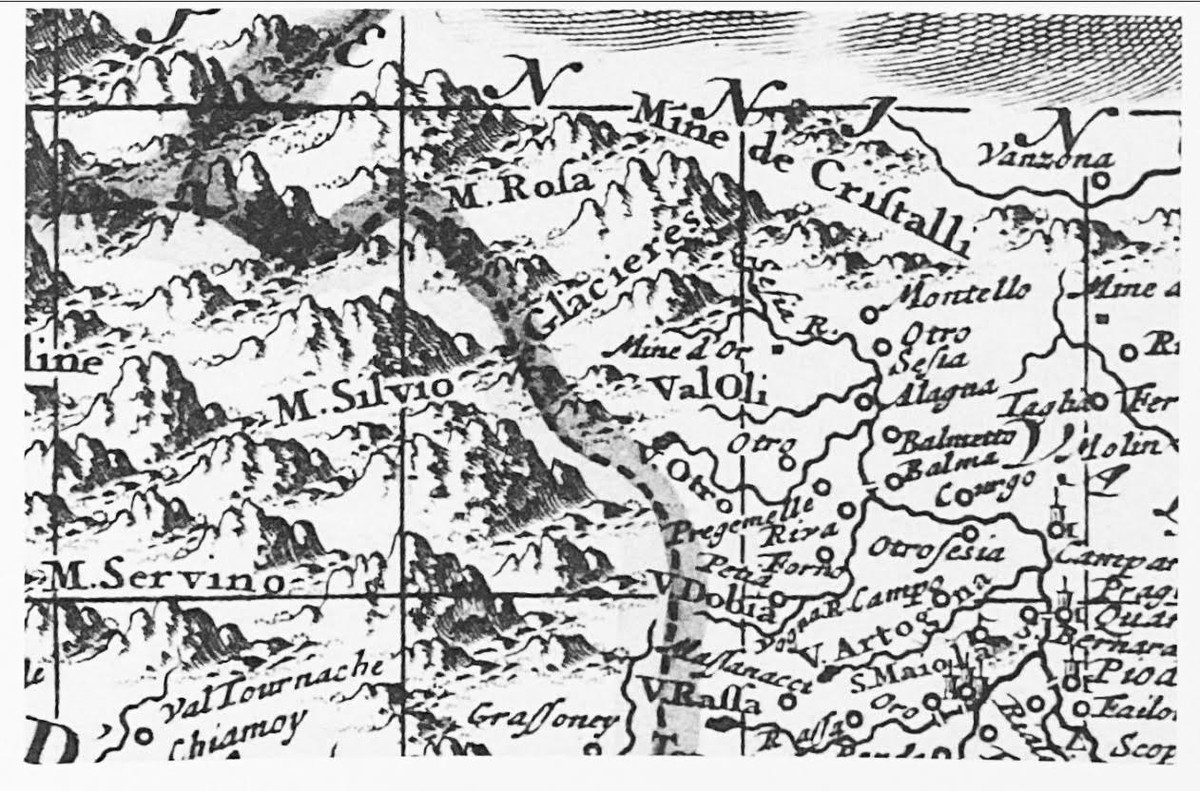

This short text belongs to a project which originally took the shape of a glossary. Its subject is not just any mountain, but a well-known and very much represented one: the Monte Rosa massif. Perhaps because it contains one of the highest peaks in Europe, or because with its glaciers it long served as a boundary, over centuries, it has been named and renamed. Its peaks were “conquered,” explored, measured, painted, written about, photographed, and mapped. This mountain, more than any other, reveals a layered strata of naming practices and eras, creating a “geological” dimension of words as much as of rock and ice.

Most of the toponyms that survived until today are the ones that got into official cartographies; therefore, those recorded during military explorations or state surveys, the systematic acts of naming that accompanied the control and exploitation of territories.

In the Western Alps, where Germanic, Romance, and Italian populations mixed across borders, mountains and even their smallest features accumulated hundreds of names long before modern state control. Some of these names made it onto maps, others survived only in oral tradition, and many have likely been lost altogether. The names that we have today form a vast geographical glossary, one that records all the ways we made sense of the mountain: a place of work, a space for imagination, a laboratory for science, a land for nationalism, and finally a playground for sports.

Toponyms, therefore, act as contextual annotations, operating at different scales and distances, much like the things they signify. Some encompass vast areas, perceptible only from afar but impossible to fully grasp up close. Others focus on a single detail, even a single rock, rendering them unrecognizable unless you are precisely there. Some describe phenomena visible only from a particular angle at a specific moment. Some are simple, descriptive names that you will find everywhere else.

Monte Rosa [45.936920, 7.866769]

Let’s start from the one, main name, for the whole thing. One of the earliest disillusions of my childhood was discovering that the name Monte Rosa did not, as I had once believed, speak of the mountain’s pink tones at sunset, but rather came from an ancient language blend (rouja) meaning quite simply, “ice.” Mountains as this one were defined by their main visual feature, having their surface covered in snow all over the year.

Col de Theodule [45.943188, 7.708797]

Mountain peaks, for much of human history, were not considered more than places to be observed: not destinations to be reached, nor features deserving individual names. They were immense presences to be circumnavigated through their accessible points – the passes. These, together with other lower elevation features such as valleys, settlements, and rivers, have perhaps the oldest name of them all: they were routes of exchange, of trade and communication, the only parts of a mountain considered relevant. Most of the toponyms of this area I’ve found recorded before 1800, were all places below 3500 meters of elevation. This specific name recalls Saint Theodore (a Swiss catholic bishop from the adjoining region) which evokes the long tradition of germanic migration and church control over the area. While today the pass is permanently covered by the thick snows of the nearby glacier, during the Middle Ages and warmer conditions, it was accessible, providing a safe route for the movement of people and goods.

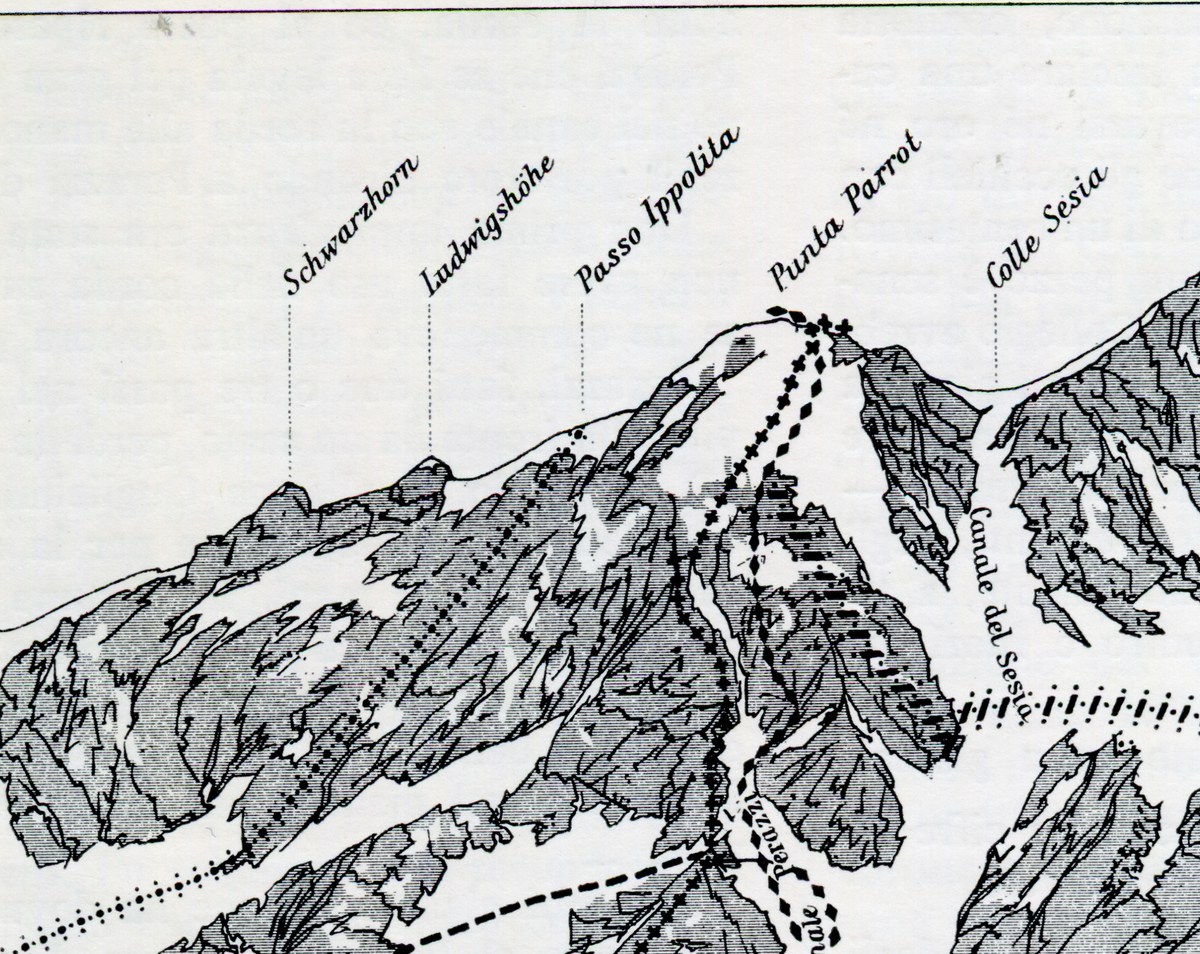

Corno Nero [45.914646, 7.861876]

At that time, when the highest lands were considered dangerous zones not to be entered, many mountain names were purely descriptive, drawn from their visible appearance when seen from somewhere lower: we still find some of these examples in names as Corno Nero (Black Horn), Schwarzberg (Black Rock), Weisstor (White Tower), Monte Moro (Dark Mountain).

These were places of which people had no direct physical experience yet (were not reached) and were not places of work (not height at which you could hunt, collect plants or breed animals). Therefore they existed just at a distance.

“White” (weiss) belonged to those peaks which were year-long covered in snow; “black” (schwarz), on the contrary, defined the ones generally keeping a dark color through seasons, therefore the ones with exposed rock faces and steep slopes. These names are very common and can still be found in any other valley. At a certain elevation, mountains were looking either snowy or rocky, and these names were classifiers rather than individual descriptions. None would actually want to reach one of these places, but perhaps just identify where the world would end and the ice would start.

The Lost Valley [45.921666, 7.843766]

The presence of the glacier and its prominent mountains are still impressive today, and not looking at them is barely impossible. Its white slopes in full summer stands out visually and they remind of another world. It’s therefore possible to imagine that these lands were the perfect setting for the creation of myths and apparitions, but also curses and darkness. Some toponyms keep these imaginative stories alive, such as the myth of a disappeared town, an imaginary place said to have existed in a “lost valley” in the middle of the glacier long before the snow covered it all. The tale may have arisen from a simple misreading of the landscape – someone mistaking a distant view of Switzerland for a nearby valley – or perhaps from deeper fears of the glacier advancing through the mountains. In 1778, the myth and reality briefly met when seven mountaineers decided to go on an expedition in search of this lost town. Although it was never found, the peak reached was called after a discovery that never happened, but recording the beginning of a different era: the end of the fearful time and the beginning of the explorations. The story survived through the toponym Punta Felik (the name of the lost town) and Roccia della Scoperta (“rock of the discovery”).

H [45.936920, 7.866769]

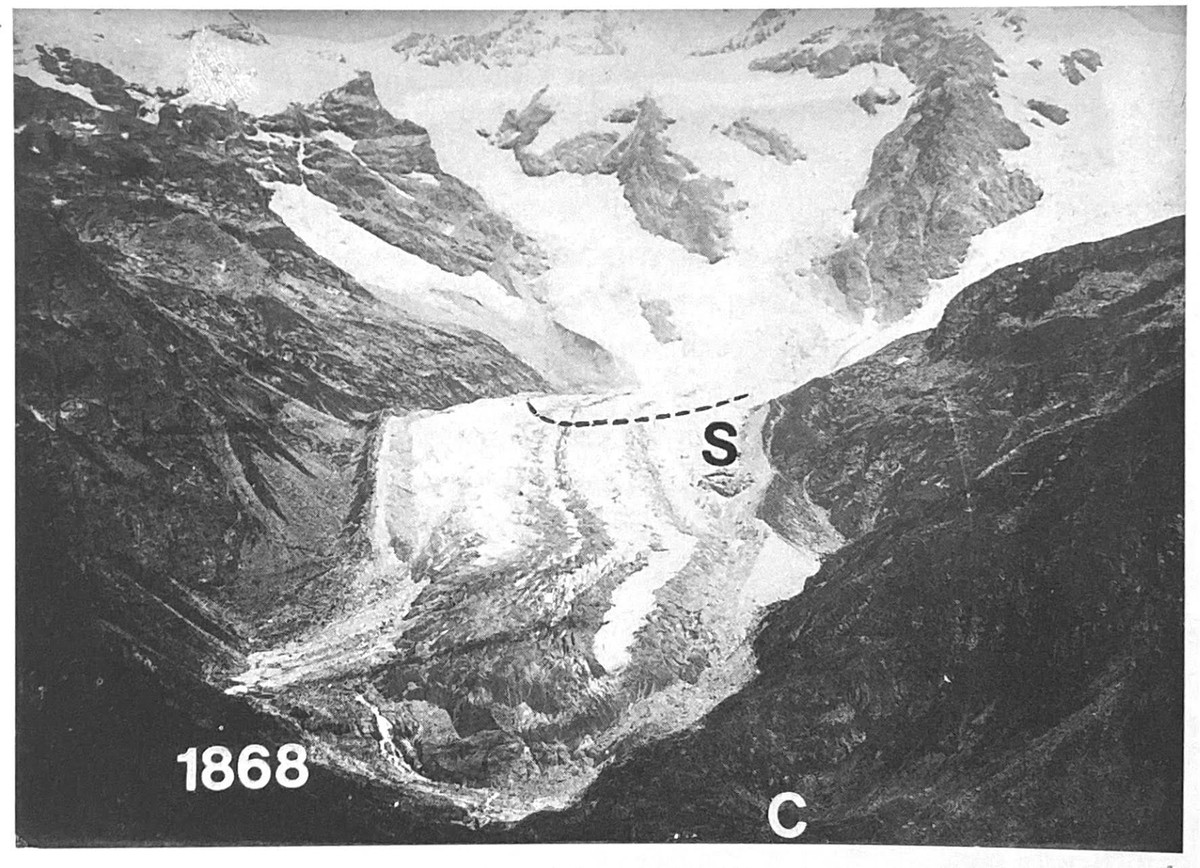

The number of toponyms and the amount of expeditions, new routes and people interested in these places were of course growing fast. Before having actual names, the major highest points were first organized in 1820 by a local called Joseph Zumstein as peak A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, and I, in height order. Defining the highest point of them all was soon the main ambition. This first attempt was in the end wrong in measurement and the highest peak was later assigned to H.

Spitze Ohne Name [45.913571, 7.857928]

The actual starting point of this work was originally when I found a weird toponym, “Spitze Ohne Name”, which means Peak without a name, a placeholder label given in 1824 to a summit of the Monte Rosa massif. Like many place-names, this one may have truly existed only in a map, in this case the one drawn by Ludwig von Welde, an Austrian army general known to be one of the first to fill with words the blank spaces of those vast, iced lands. With this name, he started to chart what at that time had only been reached by few and observed from far by many. He even named without having any idea what name to give, because a map demanded no empty space.